This Dr. Axe content is medically reviewed or fact checked to ensure factually accurate information.

With strict editorial sourcing guidelines, we only link to academic research institutions, reputable media sites and, when research is available, medically peer-reviewed studies. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to these studies.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

This article is based on scientific evidence, written by experts and fact checked by our trained editorial staff. Note that the numbers in parentheses (1, 2, etc.) are clickable links to medically peer-reviewed studies.

Our team includes licensed nutritionists and dietitians, certified health education specialists, as well as certified strength and conditioning specialists, personal trainers and corrective exercise specialists. Our team aims to be not only thorough with its research, but also objective and unbiased.

The information in our articles is NOT intended to replace a one-on-one relationship with a qualified health care professional and is not intended as medical advice.

What Are Psychotropic Drugs? Its Types, History & Statistics

October 18, 2018

One of the most controversial subjects in today’s natural health world is that of psychotropic drugs. Also referred to as psychoactive drugs, these medications make up a long list of both legal and illegal substances that affect the way the brain functions, either in an effort to treat a mental illness of some kind or for illicit recreational purposes.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, approximately one in five adults in the U.S. experiences some form of mental illness in a given year. (1) The overwhelmingly common treatment method for these illnesses has become drug therapy first, all other methods second (or not at all).

Why is it controversial? From the research I have done, I think it is due to a combination of a) the complex nature of the development and sale of psychotropic drugs, b) the many dangers of psychotropic drugs and the overall question of whether or not the benefits of these medications outweigh the risks and c) the questionable and possibly unethical financial underpinnings of the pharmaceutical industry with clinicians who treat these illnesses.

See these related articles:

- The Chemical Imbalance Myth

- Antidepressant Withdrawal Symptoms

- Dangers of Psychotropic Drugs

- Natural Alternatives to Psychiatric Drugs

“The Maudsley Debate”

In a popular dialogue published in 2015 known as the Maudsley debate, Dr. Peter Gøtzsche (a Danish physician, medical researcher and head of the Nordic Cochrane Center) and Dr. Allan H. Young (professor of mood disorders at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neurosciences in King’s College London, UK) reviewed the evidence on psychoactive drugs and their benefits versus risks. (2)

Gøtzsche, an outspoken opponent to the use of most psychoactive drugs, says in this debate that, “Psychiatric drugs are responsible for the deaths of more than half a million people aged 65 and older each year in the Western world, as I show below. Their benefits would need to be colossal to justify this, but they are minimal.”

He goes on to explain how the study designs of many trials used to evaluate and legalize many of these drugs don’t truly capture the effects of many of these medications and claims that reports on serious side effects are extremely under-reported (such as suicides while on certain antidepressants). His final conclusion?

Given their lack of benefit, I estimate we could stop almost all psychotropic drugs without causing harm — by dropping all antidepressants, ADHD drugs, and dementia drugs (as the small effects are probably the result of unblinding bias) and using only a fraction of the antipsychotics and benzodiazepines we currently use. This would lead to healthier and more long lived populations. Because psychotropic drugs are immensely harmful when used long term, they should almost exclusively be used in acute situations and always with a firm plan for tapering off, which can be difficult for many patients. We need new guidelines to reflect this. We also need widespread withdrawal clinics because many patients have become dependent on psychiatric drugs, including antidepressants, and need help so that they can stop taking them slowly and safely.

Keep in mind, Dr. Gøtzsche is the head of a Cochrane center of research, an organization recognized for their lasting commitment to solid, “gold-standard” science and truth in research.

Of course, not everyone feels this way. The other physician featured in this scientific debate claims that psychoactive drugs are no less complex and just as full of risks versus benefits than any drug used for any other medical condition. He believes these medications are safe because of the type of research they require to be approved by regulatory bodies, and that insisting they are dangerous is incorrect.

I’ll outline both legal and illegal forms of psychotropic drugs throughout this piece, but the major dangers and natural alternatives will focus mostly on legal, prescription psychotropic medications, as they have been studied more extensively.

What Are Psychotropic Drugs?

Put simply, psychotropic drugs include “any drug capable of affecting the mind, emotions and behavior.” (3) This includes common prescription medications like lithium for bipolar disorder, SSRI’s for depression and neuroleptics for psychotic conditions like schizophrenia. The list also contains street drugs like cocaine, ecstasy and LSD that create hallucinatory effects.

Why are these medications so controversial?

The controversy here is many-sided, but one of the major reasons many people have begun to question the excessive prescribing of psychoactive medications has to do with financial ties between pharmaceutical companies and people in the psychiatric field, such as researchers, practicing psychiatrists, DSM panel members and even primary physicians who prescribe treatments without specialist intervention.

For example, graduate students at the University of Massachusetts and Tufts University published a review of financial ties of DSM panel members to the financial industry in 2006, before the release of the DSM-IV. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is essentially the “bible” of psychiatry and is used to define, diagnose and determine treatment for all mental, behavioral and personality disorders.

In this review, 56 percent of the panel members, who are trusted to create diagnoses and treatment protocols based strictly on solid science, had financial associations with the pharmaceutical industry. Every single panel member determining the criteria for ‘Mood Disorders’ and ‘Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders’ was financially tied to the pharmaceutical industry — that’s especially significant, as those two areas are ones where “drugs are the first line of treatment.” (4)

These conflicts of interest also spill over into questions of the ethics of direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising for psychotropic drugs. Studies estimate that up to 70 percent of people on antidepressants have been exposed to DTC advertising for these medications. (5) Since this exposure information has been associated with increased frequency of prescription, higher costs and lower quality of prescribing, DTC advertising has been one hot topic of discussion in the ethics of psychotropic drugs. (6)

Dr. Giovanni A. Fava, a clinical psychiatrist at the University of Bologna and clinical professor of psychiatry at the University at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, puts his concerns into this alarming statement: (7)

The problem of conflicts of interest in psychiatry does not appear to be different from other fields of clinical medicine. It can be addressed only by a complex effort on different levels, which cannot be postponed any longer. In fact, either clinical researchers become salespeople (and the main aim of many scientific meetings today is apparently to sell the participant to the sponsor) or they must set out boldly to protect the community from unnecessary risks.

Types of Psychotropic Drugs

This list is not exhaustive, but contains most of the psychotropic drugs found in the United States. They are broken down into legal and illicit drugs, then further by the individual class class of medication. I have not listed medications often prescribed “off-label,” meaning not approved by the FDA for the specific condition listed but still frequently prescribed for that condition. Brand names are listed in parentheses.

Note: caffeine, tobacco and alcohol are considered psychoactive drugs. They are not listed below because they are not prescribed for any condition but are also legal substances.

Legal Psychotropic Drugs (8)

Antidepressants

- SSRIs

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Citalopram (Celexa)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

- Paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, Brisdelle)

- Escitalopram (Lexapro)

- Vortioxetine (Trintellix, )

- SNRIs

- Venlafaxine (Effexor XR)

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta, Irenka)

- Reboxetine (Edronax)

- Cyclics (tricyclic or tetracyclic, also referred to as TCAs) (9)

- Amitriptyline (Elavil)

- Amoxapine (Asendin)

- Desipramine (Norpramin, Pertofrane)

- Doxepin (Silenor, Zonalon, Prudoxin)

- Imipramine (Tofranil)

- Nortriptyline (Pamelor)

- Protriptyline (Vivactil)

- Trimipramine (Surmontil)

- Maprotiline (Ludiomil)

- MAOIs (10)

- Rasagiline (Azilect)

- Selegiline (Eldepryl, Zelapar, Emsam)

- Isocarboxazid (Marplan)

- Phenelzine (Nardil)

- Tranylcypromine (Parnate)

- Bupropion (Zyban, Aplenzin, Wellbutrin XL)

- Trazadone (Desyrel)

- Brexpiprazole (Rixulti) (antipsychotic used as an adjunctive therapy for major depressive disorder)

Anti-Anxiety Medications (Anxiolytics)

- Benzodiazepines

- Clonazepam (Klonopin)

- Alprazolam (Xanax, Alprazolam Intensol, Xanax XR)

- Lorazepam (Ativan, Lorazepam Intensol)

- Prazepam (Centrax)

- Oxazepam (Serax)

- Clorazepic acid (Tranxene)

- Diazepam (Valium, Diastat, Diazepam Intensol)

- Buspirone (BuSpar)

- Chlordiazepoxide (Librium)

ADHD Medications

- Stimulants

- Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, Daytrana, Methylin)

- Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine (Adderall)

- Dextroamphetamine (ProCentra, Dexedrine Spansule, Zenzedi)

- Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate (Vyvanse)

- Pemoline (Cylert)

- Atomoxetine (Strattera)

Antipsychotics

- Neuroleptics (“Typical” antipsychotics) (11)

- Chlorpromazine (Thorazine, Largactil)

- Haloperidol (Haldol)

- Perphenazine (Trilafon, Etrafon/Triavil/Triptafen, Decentan)

- Fluphenazine (Prolixin, Modecate, Moditen)

- Loxapine (Loxitane)

- Thioridazine (Mellaril)

- Molindone (Moban)

- Thiothixene (Navane)

- Trifluoperazine (Stelazine)

- Brexpiprazole (Rixulti)

- “Atypical” Antipsychotics (second generation)

- Risperidone (Risperdal)

- Olanzapine (Zyprexa)

- Quetiapine (Seroquel)

- Ziprasidone (Geodon, Zeldox, Zipwell)

- Aripiprazole (Abilify, Aristada)

- Paliperidone (Invega)

- Lurasidone (Latuda)

- Clozapine (Clozaril)

Mood Stabilizers (for seizure disorders, bipolar depression, unipolar depression, schizoaffective disorder, impulse control disorders and certain pediatric mental illnesses)

- Anticonvulsants

- Valproic acid (Valproic, Depakene)

- Carbamazepine (Tegretol, Carbatrol, Epitol)

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal, Oxtellar)

- Lithium

Anti-obsessive Agents (for obsessive-compulsive disorder) (12)

- Clomipramine (Anafranil)

- Fluvoxamine (Luvox)

- Paroxetine (Paxil)

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

Anti-Panic Agents (for panic disorder)

- Clonazepam (Klonopin)

- Paroxetin (Paxil)

- Alprazolam (Xanax)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

Hypnotics (for sleep disorders and (sometimes) anxiety) (13)

- Barbiturates

- Secobarbital (Seconal)

- Mephobarbital (Mebaral)

- Pentobarbitol (Nembutal)

- Butabarbital (Butisol Sodium)

- Phenobarbitol (Luminal)

- Amobarbital (Amytal Sodium)

- Benzodiazapenes

- Clonazepam (Klonopin)

- Alprazolam (Xanax, Alprazolam Intensol, Niravam)

- Lorazepam (Ativan, Lorazepam Intensol)

- Prazepam (Centrax)

- Oxazepam (Serax)

- Clorazepic acid/Clorazepate (Tranxene)

- Diazepam (Valium, Diastat, Diazepam Intensol, Zetran)

- Estazolam (Prosom)

- Quazepam (Doral

- Chlordiazepoxide (Librium)

- Flurazepam (Dalmane)

- Triazolam (Halcion)

- Temazepam (Restoril)

- Midazolam (Versed)

- Clobazam (Onfi)

- Diphenhydramine (Allermax, Benadryl)

- Zolpidem (Ambien, Edluar, Intermezzo, Zoplimist)

- Tryptophan (Aminomine)

- Hydroxyzine (Atarax, Hyzine, Vistaril)

- Diphenhydramine (Banophen)

- Suvorexant (Belsomra)

- Buspirone (BuSpar, Vanspar)

- Doxylamine (Care One, Doxytex, Equaline Sleep Aid, Equate Sleep Aid, Unisom SleepTabs)

- Tasimelteon (Hetlioz)

- Eszopiclone (Lunesta)

- Meprobamate (Miltown)

- Ethchlorvynol (Placidyl)

- Dexmedetomidine (Precedex)

- Ramelteon (Rozerem)

- Doxepin (Silenor, Sinequan)

- Chloral hydrate (Somnote)

- Zaleplon (Sonata)

- Sodium oxybate (Xyrem)

Illegal Psychotropic Drugs (14)

- MDMA (ecstasy, Molly, E)

- MDA (Sally)

- Sassafras (brown sugar Molly)

- 6-APB (Benzo Fury)

- Alpha-Methyltryptamine (spirals)

Stimulants

- Cocaine (coke)

- Crack cocaine (crack)

- Methamphetamine (meth, crystal meth)

- Amphetamine (speed)

- MDMA (ecstasy, Molly, E)

Depressants (usually illegally administered prescription drugs, street names listed here)

- Marijuana (weed, grass)

- Barbs

- Candy

- Downers

- Phennies

- Reds

- Red birds

- Sleeping pills

- Tooies

- Tranks

- Yellows

- Yellow jackets

Hallucinogens (15)

- LSD (acid)

- Psilocybin (shrooms, caps)

- Peyote (bad seed)

- PCP (angel dust)

- Salvia divinorum (leaves of Mary)

- MDMA (ecstasy, Molly, E)

History of Psychotropic Drugs

In Psychopharmacology: Practice and Contexts, the author explains that modern psychotropic drug treatment began with two discoveries: “chlorpromazine as a treatment for psychosis, and the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) in the early 1950s.” Then, diazepam (brand name Valium®) was introduced to help treat anxiety and insomnia, replacing the nervous system depressants (barbiturates) such as morphine that had been used in the past. This was notable because of the many side effects of barbiturates, such as elevated suicide risk.

From 1990–1999, the Library of Congress and the National Institute of Mental Health played out a resolution that would define this time as what is now known as “the decade of the brain.” Specifically, these organizations sought to increase awareness of the benefits of brain research. At that point, prescribing psychotropic drugs became a booming business, raking in many billions of dollars each year and paying out billions to influence clinicians to prescribe, prescribe, prescribe! (16)

These days, it’s estimated that the “global depression drug market” (including only the largest class of many psychotropic drugs) will reach $16.8 billion USD in 2020, up from $14.51 billion in 2014. (17)

Fascinatingly, though, there is a thread through this history that many have never even been made aware of: the fight to rid the world of psychoactive medications.

The Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) is a non-profit mental health “watchdog” organization that has been battling mental health industry abuses since 1969. In their 2008 exposé, CCHR gies a timeline dating back to 1978 on the events that led them to believe that SSRIs and other psychoactive drugs were much less effective and far more dangerous than consumers were being told, and the outline of their legal battles along the way. (18) They highlight more of the history of psychotropic drugs than most documents present.

For example, they explain that fluoxetine (brand name Prozac®), the first FDA-approved SSRI, was given permission to be sold on the basis of three studies. In one study, no improvement versus placebo was noted; in the second, fluoxetine was inferior to imipramine (an older TCA) but better than placebo; and in the third study, fluoxetine performed better than placebo in reducing signs of depression (in 11 patients over just five weeks of study).

Various side effects and severe adverse reactions were not reported to the FDA in the initial New Drug Application for fluoxetine. The medication was still approved on December 29, 1987. Over a decade later, lawsuits would reveal that the manufacturer had prior knowledge of not only many safety concerns but also a highly elevated risk of suicidal thoughts in patients taking the medication.

In 1990, Dr. Martin Teicher of Harvard Medical School published a study about suicide and fluoxetine treatment, explaining that taking this medication was associated with “intense, violent suicidal thoughts” in a large number of patients. (19) No action was taken by regulatory bodies at that time.

An FDA safety reviewer, Andrew Mosholder, MD, was interviewed in 1994 at a hearing with the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee of the FDA (PDAC) about a trial for fluoxetine and its effects on bulimia, an eating disorder. He presented the study results: seven patients in the study died, four of them definitely by suicide. None of the bodies were autopsied. In addition, the manufacturer of the drug stated in their package information that nine percent of clinical trial patients developed anorexia. Even so, fluoxetine was approved as a treatment for bulimia after this hearing. (18)

Joseph Glenmullen, MD, a Harvard Medical School psychiatrist, released a book called Prozac Backlash in 2001, detailing SSRI dangers including neurological disorders like facial and whole body tics were becoming of increasing concern for patients on these medications. In his book, he likens SSRI’s to a “chemical lobotomy” that destroys brain nerve endings.

The FDA finally made a move to protect children from the well-documented suicidal behaviors associated with SSRIs particularly common in children and adolescents, issuing an advisory warning on July 5, 2005 that “suicidal thoughts and behaviors can be expected in about 1 of 50 treated pediatric patients.” (18)

Just two weeks later, the same manufacturer now tasked with adding additional warnings to fluoxetine labels (Eli Lilly) agreed to pay $690 million, settling over 8,000 claims about olanzapine (brand name Zyprexa®). These claims alleged the drug was causing life-threatening diabetes. As of January 2009, they had settled over 30,000 claims, paying out $1.2 billion. (20) Also in January 2009, the U.S. Department of Justice fined Eli Lilly $515 million in a criminal fine (the largest ever criminal fine of this kind) and up to $800 million civil settlement for promoting the same medication for “off-label uses” (meaning those not approved by the FDA). (21)

In November 2005, the FDA listed “homicidal ideation” as one adverse event possible when taking venlafaxine (brand name Effexor®). The Washington Post released a story in 2006 detailing this adverse event warning and shared that infamous criminal Andrea Yates was taking the medication when she drowned her five children in 2001. The manufacturer claimed that they had found no causal link between the drug and such behaviors or desires. (22)

Alaska’s Supreme Court was tasked with ruling on the dangers of psychotropic drugs in 2006, determining in June of that year that: (23)

Courts have observed that ‘the likelihood that psychotropic drugs will cause at least some temporary side effects appears to be undisputed and many have noted that the drugs may — most infamously — cause Parkinsonian syndrome [disease of the nerves causing tremor, muscle weakness and retardation, shuffling walk and salivation] and tardive dyskinesia [slow and involuntary mouth, lip and tongue movements].

CCHR also shares that in April 2007: (18)

Over 350 lawsuits were filed in April against AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals after the FDA ordered a change in the labeling of its antipsychotic drug, Seroquel® (quetiapine), to warn users about an increased risk of diabetes. Further, Seroquel was linked to pancreatitis (an inflammation of the pancreas), hyperglycemia, and Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome, a potentially fatal syndrome with symptoms that include irregular heartbeat, fever, and stiff muscles. It could also increase the risk of death in seniors who had dementia-related mental problems, a condition that Seroquel has not been approved to treat.

So, Do Psychotropic Drugs Work?

What about their effectiveness? That’s a pretty gray area, too. For example, a scientific review on antidepressants discovered that authors were much less likely to publish studies with negative results and that studies with results interpreted as negative by the FDA are commonly spun as positive when written and published in journals. In fact, the researchers completing this review said antidepressants may have some positive effects, but that they were concerned the theory of how useful they truly are is biased, due to the lack of available data. (24)

That means all results must, unfortunately, be viewed with a grain of salt — a grain which, logically, may tend to be particularly doubtful of positive study results for the impact of antidepressants.

A 2010 Cochrane review found that SSRIs, the most commonly prescribed antidepressants, are no more effective than placebo when treating mild-to-moderate depression. They also concluded that TCAs are more effective than SSRIs, but that the side effects were generally worse. Fascinatingly, even with these extremely underwhelming results, the author points out that the studies mostly had short trial periods (four to six weeks), with four of the 14 trials following up after 12–24 weeks). In addition, pharmaceutical studies sponsored the vast majority of these studies.

These medications, according to the Cochrane piece published in American Family Physician, may only be really useful for cases of severe depression. Another 2010 meta-analysis came to the same conclusion, stating that placebo seems to be just as effective in all but severe depression cases. (25, 26)

Based on another review of depression research trials, a 2002 study found that the “true drug effect” of antidepressants was somewhere between 10–20 percent, meaning that 80–90 percent of patients in these trials either responded to a placebo effect or did not respond at all. (27)

Moving away from depression, SSRIs do seem to be effective, at least in the short term, when it comes to manic depression (also known as bipolar depression or bipolar disorder). (28)

Reviewing drugs used for ADHD, researchers at the Oregon Evidence-based Practice Center found startling results about their effectiveness (or lack thereof) in a 2005 paper. For instance, they state, “Good quality evidence on the use of drugs to affect outcomes relating to global academic performance, consequences of risky behaviors, social achievements, etc. is lacking.”

The review goes on to discuss the poor quality of studies available on ADHD-treating psychoactive drugs, explaining that they don’t use large pools of subjects, long enough study durations, functional outcomes or long-term effects.

Breaking up the review into age brackets, the researchers found that between 3-12 years of age, results were inconclusive at best and negative, at worst, with virtually no information. For adolescents, more solid information existed that some stimulants could potentially alleviate some symptoms of ADHD, but it was associated with more side effects. None of the studies in children or teens included long-term evidence of efficacy.

For adults, the limited research pointed to an effectiveness somewhere between 39–70 percent when compared to placebo, although they found unconvincing evidence regarding quality of life and other improvements expected with treatment.

When observing illegal drugs, there is no scientifically prescribed “benefit” to the user for a condition or disease. However, perceptions of active drug users have found interesting results — nearly 6,000 people were surveyed in one 2013 article, and there was no correlation whatsoever between either the U.S. or the U.K. schedules of harmful drugs, meaning that the drugs deemed most dangerous by the countries’ regulatory bodies are rated pretty low on “harms” by consumers, such as ecstasy, cannabis and hallucinogens. Users also found benzodiazepines as one class perceived to have high benefits and also high harms. (30)

Psychotropic Drug Statistics

How common are these psychoactive drugs, and what are the psychoactive drug statistics that should matter to you? Here are some numbers I think may interest you.

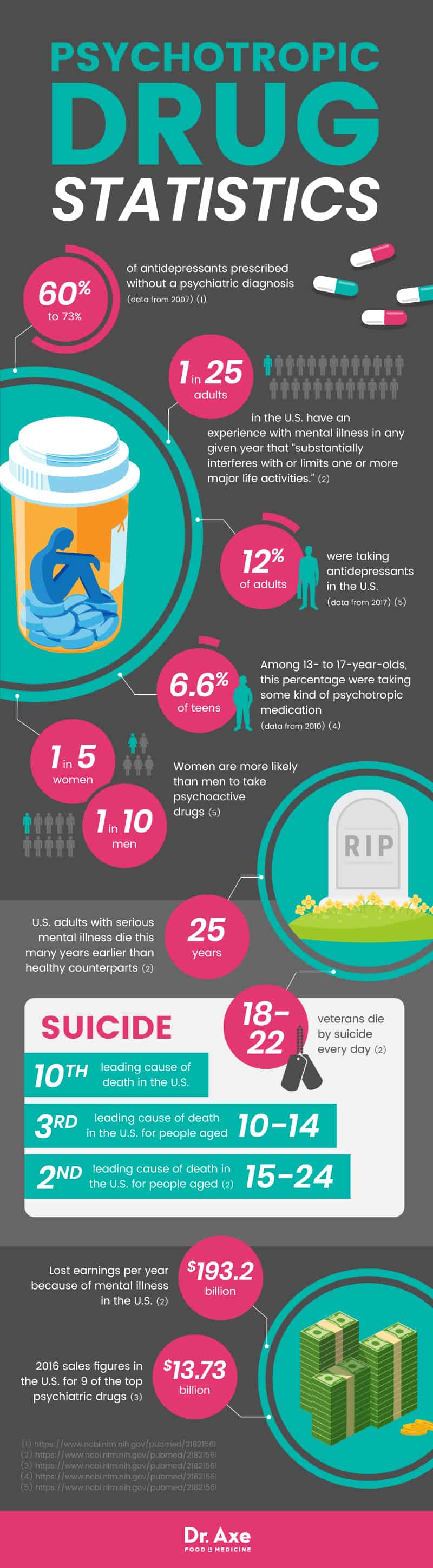

- Antidepressants were prescribed without a psychiatric diagnosis from 59.5 percent in 1996 up to 72.7 percent in 2007. (31) Generally, this occurs when a primary care physician (general practitioner) prescribes psychoactive drugs based on a person’s explanation of their condition, without referring the patient to a qualified psychiatrist or clinical psychologist.

- It is estimated that one in 25 adults in the U.S. (four percent) have an experience with mental illness in any given year that “substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities.” (1)

- “Serious mental illness costs America $193.2 billion in lost earnings per year.” (1)

- US adults with serious mental illness die an average of 25 years earlier than their healthy counterparts, due in large part to co-occurring, treatable medical conditions. (1)

- “Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S., the 3rd leading cause of death for people aged 10–14 and the 2nd leading cause of death for people aged 15–24.” (1)

- “Each day, an estimated 18–22 veterans die by suicide.” (1)

- In 2016, nine of the top psychiatric drugs totaled over $13.73 billion USD in sales. (32)

- As of 2010, 6.6 percent of adolescents between 13–17 were taking some kind of psychotropic medication, which is believed to be a conservative estimate. (33)

- As of early 2017, 12 percent of adults in the U.S. were taking antidepressants, 8.3 percents were taking anxiolytics, sedatives and hypnotics, and 1.6 percent reported taking antipsychotics. (34)

- Caucasians are much more (21 percent) likely to be on psychotropic drugs, compared to Hispanics (8.7 percent), blacks (9.7 percent) and Asians (4.8 percent). (34)

- Women are more likely than men to take psychoactive drugs, namely, one in five women versus one in 10 men. (34)

Psychotropic Drugs Precautions

It’s important to always conduct any change in medication and/or supplements under the supervision of a doctor. Withdrawal from psychotropic drugs can be very challenging and even dangerous if done cold turkey without the guidance of a healthcare professional — do not attempt to change medication schedules on your own, particularly if it would involve discontinuing the use of any prescribed medication.

Supplements count when you’re discussing drug interactions. When talking to your doctor about any medications you may be taking, include supplements on that list so that they can be fully aware of any possible interactions. This is important especially for St. John’s Wort and any adaptogen supplements that impact hormone levels.

If you are pregnant and currently taking psychoactive drugs, do not be alarmed and do not stop taking your medication unless instructed by a qualified physician or integrative practitioner. Pregnant women already on an antidepressant and who quit mid-pregnancy have a nearly three-fold relapse rate compared to those who continue their medication. (35) The risk of negative pregnancy outcomes, at least for SSRIs, is about the same for people who quit the medication mid-pregnancy versus those who take it throughout. (36)

Psychotropic drugs present a huge list of drug interactions that your doctor should already understand. However, the NIMH points out in their mental health medications index that patients should be aware that combining SSRIs or SNRIs with triptan medications used for migraines (such as sumatriptan, zolmitriptan and rizatriptan) can result in serotonin syndrome, which is a life-threatening illness involving agitation, hallucinations, high temperature and unusual blood pressure changes. It is most commonly associated with MAOIs but can also happen with newer antidepressants. (35)

There are also reports of adolescent males taking TCAs for ADHD who began to show “cognitive changes, delirium and tachycardia after smoking marijuana.” Even if marijuana is legal in your area, it should not be taken alongside other psychoactive drugs. (37)

Some SSRIs have been linked to bone fractures in older people. (38)

Final Thoughts About Psychotropic Drugs

Psychotropic drugs became a major part of the pharmaceutical industry about halfway through the 20th century. Since then, they have become the first line treatment for many psychological disorders, despite widespread concerns about their effectiveness and ethical implications, as the financial ties between industries are questionable at best.

This class of drugs also includes a number of illicit drugs, often used recreationally. Interestingly, at least a couple of these may have therapeutic benefits for certain mental conditions, according to recent research.

Many prominent physicians and researchers agree that psychotropic drugs are not the “golden cow” of psychiatry that many thought they would be; instead, they are associated with some of the most extreme side effects of pharmaceuticals and may even be causally related to the development and genetic disposition of mental illness in future generations.

Do they work? Psychoactive drugs do exert some positive effects against the disorders they aim to treat, but usually at the expense of a number of other serious risks. Some research suggests the actual effect of antidepressants may only be in about 10–20 percent of patients.

The major classes of legal psychotropic drugs include antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, ADHD medications (mostly stimulants), antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, anti-obsessive agents, anti-panic agents and hypnotics. Illicit psychoactive drugs include empathogens, stimulants, depressants and hallucinogens.

Do not ever change your medication schedule without medical supervision. Psychoactive drugs have many complex interactions with both medicines and supplements, so always give your doctor complete information when it comes to anything you may take in those forms.